Never the same: The Big East’s era as an elite basketball conference comes to an end with Syracuse’s departure

The league started as an idea. A vision in one man’s mind. A dream to make the Northeast the center of college basketball.

It required a leap of faith from six athletic directors and their coaches, the formation of a television network and the ability to pull in the best players in the country.

The Big East was born in 1979. The dream became a reality six years later when Georgetown, St. John’s and Villanova reached the Final Four in Lexington, Ky.

“It was somewhat surreal because you have to look around and say, ‘My God it’s never been done before,’” former Big East commissioner Mike Tranghese said. “We were only 6 years old and we were there.”

It’s the moment Tranghese and others point to as the conference’s arrival on the national scene. It cemented its place as the premiere league in the country and grabbed the attention of anyone who hadn’t already taken notice.

The Big East has evolved over its history, adding and losing programs as college athletics constantly changed. But as it enters its 33rd season, the conference is preparing to say goodbye to one of its founding members.

When Syracuse moves to the Atlantic Coast Conference in 2013, the Big East will lose its identity as the best conference in the country — a title it first earned during its meteoric rise in the 1980s.

***

Dave Gavitt’s grandiose vision for a basketball league had been developing for years. By January 1979, he decided it was finally time to make it a reality.

The Providence athletic director sold his dream to his counterparts from six other Northeast schools at four meetings over five months, painting a picture of a league that would provide the independent schools with a bigger stage, generate television exposure and create rivalries.

The seven-school conference was established in the following September. There were only two employees — Tranghese and a secretary — and they worked out of an office leased in Duffy & Shanley public relations firm in Providence, R.I.

“We were running the thing by our shoestrings,” said Tranghese, who was Gavitt’s right-hand man and the league’s commissioner from 1990 to 2009. “And we did everything from managing this little office to doing PR and marketing to scheduling championships to running the basketball tournament.”

Gavitt, who served as the acting commissioner while remaining at Providence until 1982, directed Tranghese as he also worked to create the Big East television network.

The games would be syndicated on independent stations in New York, Boston and Washington, D.C., among others, broadcasting a “Monday night game of the week.”

But the first matchup billed as a “Monday night game” on the conference’s network was played on a Wednesday between Seton Hall and Ivy League opponent Princeton. The bizarre television debut continued when Len Berman began his postgame broadcast and Walsh Gym was immediately enclosed in darkness.

The lights to the arena had been shut off.

“That’s how far the league came from very, very humble beginnings,” said Berman, who was the first television announcer for the Big East.

Those humble beginnings provided a solid foundation for the future.

Big East games were soon featured on delay by a fledgling sports television network called ESPN. And the pillars of the league — Syracuse, Georgetown and St. John’s — all finished the first season ranked in the top 13 in the nation.

“The steps were small at the beginning, but obviously very quickly the league took off,” Tranghese said.

***

The league meeting rooms became battle zones.

The coaches went at each other, getting into shouting matches over everything from recruiting to officiating. Tranghese remembers the tense atmosphere well, but said he can’t reveal the details of the fierce arguments.

Gavitt made it clear the spats could never leave the room.

“He said, ‘In the room, you can say whatever you want, but when we leave here, we’re a family and we promote,’” Tranghese said. “And that’s what everybody did.”

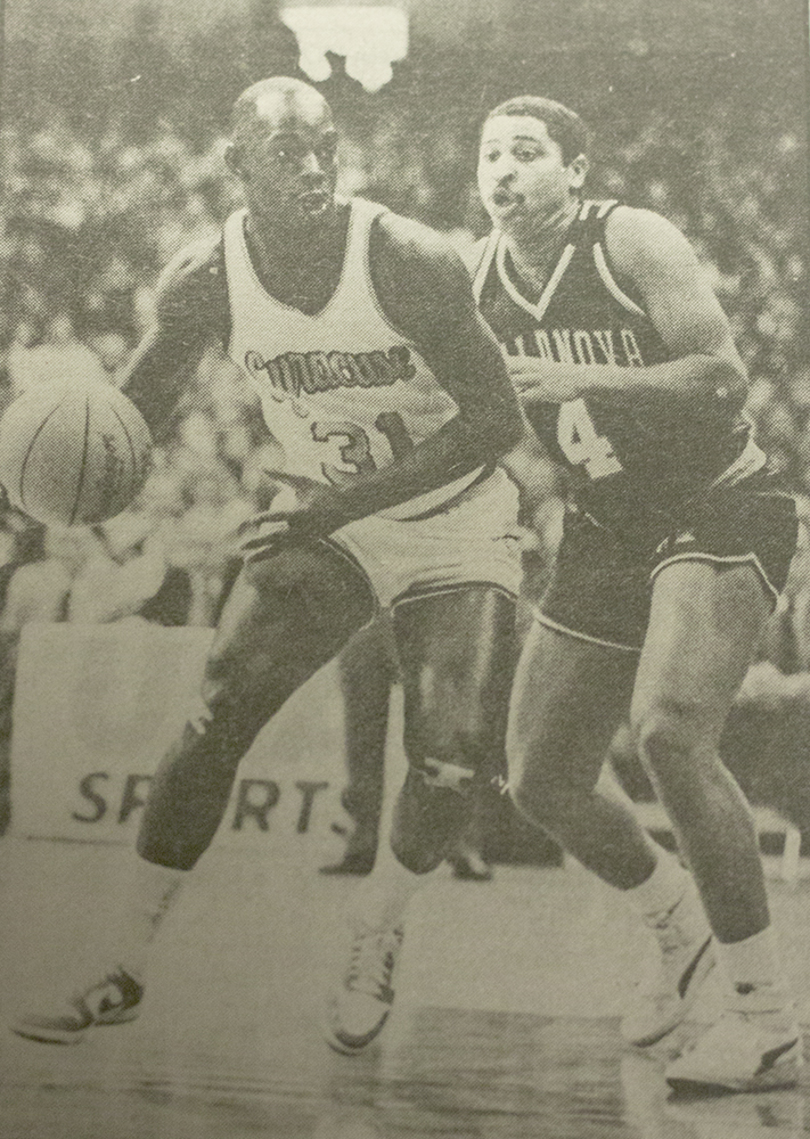

The coaches were at the heart of the conference’s birth and its rise to prominence. Jim Boeheim, John Thompson, Lou Carnesecca and Rollie Massimino all became names synonymous with winning and the Big East.

The battles spilled from the league meetings onto the court as their programs emerged as the conference’s elite. They all had their own styles in a tough, physical league, and their personalities grew with the conference’s popularity thanks to the television deal with ESPN.

Those personalities left Steve Lappas in awe at his first league meeting in 1984. An assistant coach at Villanova, Lappas compared the experience to being “like a kid in the candy store” as he sat alongside the biggest names in college basketball.

“Those guys were the all-time coaches and Jim Boeheim is still doing it,” said Lappas, now an analyst for CBS Sports Network. “Their recruiting, their coaching and their personalities were the things that made this league what it was.”

The Big East’s growth was playing out just how Gavitt had envisioned.

The coaches came together to promote the new league, and the television exposure gave them everything they needed to land the best players on the recruiting trail.

***

Thirty years later, those coaches are legends. But those who witnessed the Big East at its peak say it was a “players’ league.”

It all started with the 1981 freshman class highlighted by Georgetown center Patrick Ewing and St. John’s guard Chris Mullin. Two years later, a guard out of Brooklyn named Dwayne “Pearl” Washington — the No. 1 recruit in the nation — arrived at Syracuse.

“We don’t do anything without those players,” Tranghese said. “It’s as simple as that.”

All-time great rivalries formed around those stars. Monday night broadcasts on ESPN became an event because of them. The Big East became best conference in college basketball.

Tranghese called Ewing the best player to ever play in the Big East. He said Chris Mullin was the best shooter he ever saw in the college game while Pearl was “without question the most exciting, creative player” in the league’s storied history.

Former Georgetown coach Craig Esherick counts Mullin and Washington among the five toughest players his teams ever had to face.

“As a coach, you always measure the quality of the player by how happy you are when they’re taken out of the game by the opposing coach,” Esherick said. “And I can’t tell you how happy we were when Chris Mullin and Pearl Washington were taken out of the game.”

Washington brought his famed crossover dribble to Syracuse from New York City and captivated Big East fans with his flashy style of play.

“Every place that I went to, it was always the same way,” Washington said. “People wanted to see Pearl Washington play.”

Washington said even he is amazed at the shows he put on when he watches old tapes of his glory days before recalling a particular memory in the Big East tournament at Madison Square Garden.

The Syracuse guard dribbled his way through three players on the vaunted Georgetown defense, leaving Ewing all alone waiting for him in the paint.

“When I went up to the other side of the basket, he didn’t even jump,” Washington said. “And you know that’s not Patrick Ewing because Patrick Ewing tries to get everything. He tries to block every shot.

“But I think what he was so confused about when he saw me get by those guys like that and he was watching by the time I got to him, it was like he couldn’t even move.”

Washington said with a laugh that he can understand how Ewing got caught watching the show. The Georgetown center and Mullin took center stage, too, like when they met for the eighth time during the regular season in their careers in a historic No. 1 vs. No. 2 matchup at the Garden in 1985.

Those players are what Esherick said he’ll remember when he thinks back to the original Big East. They’ll also be the lasting memory for Berman.

“You think of the big names, you think of the players,” Berman said. “The players made it.”

***

John Thompson III grew up with the Big East. A quick look through the conference’s media guide doubles as a trip down memory lane for the Georgetown head coach.

He was at “The Sweater Game” in 1985. And he was at so many Big East tournaments in Madison Square Garden, watching intently as his father’s teams fought for conference supremacy.

As he scanned the ninth floor of the New York Athletic Club at Big East media day in October, Thompson III said he still sees a conference defined by the same principles of Gavitt’s vision 33 years ago.

“Much like then, we have a group of teams in this room that are going to be among the best teams in college basketball,” Thompson III said. “You have a group of coaches in this room that are among the best in college basketball. You have a lot of players in this room that are the best in college basketball.”

The league has maintained that reputation despite a constant evolution that saw it balloon to 16 teams in 2005 and dropped to 15 programs this season after West Virginia’s departure.

“The league is still here, it’s still very good and it will still be very good in the future,” Boeheim said. “It’s constantly changed and it’s always been good.”

Though the Big East hasn’t been what Washington and others consider the “true” Big East for years, the pillars of SU, St. John’s and Georgetown kept the connection to its proud past alive.

But when Syracuse leaves after this season, the Big East will be the same conference in name only. The league built by Ewing, Mullin, Washington and the legendary coaches will become a memory without its flagship member.

“People have come and gone, but Syracuse was a staple,” Lappas said. “Syracuse was always there. With Syracuse gone, that is a tremendous void for the league.

“Is it still a good league? Sure, it’s still a good league. But it will never be the same.”

Published on November 8, 2012 at 2:57 am

Contact Ryne: rjgery@syr.edu

Related Stories

- Wave of the future: Hopkins spends his career perfecting coaching model as he prepares to take helm at Syracuse

- Transcending time: Syracuse players recall witnessing captivating moments in Big East history

- Building mystique: The Carrier Dome proved to be a key factor in the Big East's growth during the 1980s

- The Top 10: A rundown of the all-time highlights for Syracuse in its proud run in the Big East

- Ollie looks to make his own mark on the Connecticut program built by Calhoun